I stood on the sidewalk in downtown Anchorage waving a purple and red sign that said “North with you! :)” Sarah was 50 feet in front bobbing double thumbs up to the oncoming traffic. Her bright pink jacket helped to catch people’s attention. Nine rides later, the equivalent of driving from San Francisco to Seattle, we stepped out of an 18-wheeler at the beginning of the route we drew in Google Earth. From there, we walked and rafted west nearly to Kotzebue. 524 miles in total. Across the equivalent of several Northeastern states. Without roads or trails.

BROOKS RANGE 101

- 11,800 people and 235,000 caribou live in far north Alaska, an area the size of California. 39 million people and zero caribou live in California.

- Gates of the Arctic National Park, the size of Maryland, sees perhaps 500 annual visitors and has no recreation infrastructure (trails, toilets, bridges, etc.)

- 120 million year old mountains range from 3,000-9,000 feet in elevation.

- The near absence of glaciers make long distance travel possible without technical skills; unlike most ranges in Alaska, you don’t need to be a ski mountaineer to experience the landscape.

![]() |

| Our route in red. |

GPS coordinates of our campsites, wildlife sightings, and the 132 antlers that came within 30 ft. of our path are here. Our gear list and commentary are here.THE HITCH Arguably to a greater degree than elsewhere, people in Alaska care a lot about how much time they’ve spent in the state. The longer you’ve been here the better. Double bonus if you were born in the state. Growing up a bush community gives you mad ups.

One of the men we rode with told us “I’m born and raised and I’ve never left!”

“Never left?!” I asked.

“Well,” he confessed, “I rode my motorcycle into Canada once.”

The crux of the hitch was getting a ride from Fairbanks north to the start of our route. Most of the traffic on the Haul road is commercial—truckers pulling food, fuel, and equipment; pipeline workers; geologists and ecologists employed by extractive industries and the institutions that regulate them—folks who are prohibited from picking up passengers. At Hilltop Truck Stop, the last commercial entity before the road turned to dirt and became remote, Sarah spent a few fruitless hours asking truckers if we could go north with them while I spent a few fruitless hours waving the sign by the side of the road. Eventually, she became tired of soliciting the truckers and asked me to take over. The first man I asked said, “Sure, I don’t mind.”

Meet Dick Brennan, grandpa and Haul road. veteran. He helped to build the road in the 1970’s and has logged three million miles on it since then. That’s the time equivalent of spending 16 continuous years of his life traveling between Fairbanks and Prudhoe Bay. Naturally, we learned some trucker jargon:

“Shake the load loose” = get started

“Four wheeler” = car or truck with four wheels

“Keep your foot in it” = don’t slow down

“Blow” = winter storm. Bad blows have kept him idling, stationary, for five days. “Sometimes you can’t see your hand outstretched in front of your face.”

At his office, Dick manipulates pedals, shifters, and buttons while witnessing the Arctic landscape transition from winter to summer and back again. During the colder months, when oil and gas activity peaks, he drives on ice roads up to and out on the Beaufort Sea. In the summer he watches moose, caribou, and millions of migrating birds from his triple thick windows. We averaged 2.4 mpg over the 310 miles to our desired drainage, then Dick continued north pulling a 60,000 lb. oil-water separator.

![]() |

| Thanks to Dick Brennan for bringing us the final 310 miles. |

HAUL ROAD TO ANATUVUK PASS (60 miles)

Hugging the continental divide, this was the easiest walking we encountered. The weather was perfect, the tussocks sparse, and the caribou antlers prolific. We planned to take four days to get to Anatuvuk and did just that; we slept in until 10, took photos and Gaia GPS locations for all 115 antlers that came within 30 feet of our path, marveled at permafrost sink holes, talked and cried about commitment in our relationship, and enjoyed long lunch breaks in the sun.

![]() |

| We called this a "permafrost sink hole" |

![]() |

| Melting soil |

![]() |

| Caribou antlers!! |

![]() |

| Musk ox |

ANATUVUK PASS (0 miles)

We expected to walk into town, find the post office, pack our bags with the goods we mailed there, and walk out of town an hour later. However, we ended up walking out of town one week later!

We learned the post office had been closed for the previous three days because the post mistress was at a hospital in Fairbanks caring for her sick baby boy. Neither the store employees, the policeman, the ranger, nor folks on the street knew when she would be back. Sleeping at various locations outside of town, we walked to the airstrip each day at 9 a.m. and 4 p.m., hoping to see her step off a plane.

Bush Alaska continues to exist in large part because the United States Postal Service contracts with flight services for daily mail delivery. This dramatically lowers the cost for flights to regional hubs, and allows people to get free shipping from Amazon and have fresh food delivered from Fred Meyer. One man we talked to was waiting for a trampoline ($90 with free shipping). A sport hunting guide was waiting for dog food ($20 per bag with free shipping). Like us, other visitors were waiting for resupply food: ten NOLS style hikers from Wisconsin, two hikers from Switzerland, and two hikers from California and the UK.

We purchased calories from the Nunamiut store and debated whether things were cheap or expensive. A small loaf of preservative-filled bread cost $8. Bananas were $2.50 each. Ripe bananas from Ecuador to an Arctic village for only $2.50 each! Sarah couldn’t resist.

We spent several days talking with Al Smith, Anatuvuk’s National Park Service ranger. He is the most impressive ranger I’ve ever spoken with: engaged in the local community, immensely knowledge about its history and culture, and an excellent teacher. We asked him questions hour after hour, day after day, excitedly following down history’s winding paths, our eyes jumping from wall to wall as he referenced the maps, books, and articles that covered every square inch of the office (see photo below).

![]() |

| Learning from Gates of the Arctic National Park Ranger Al Smith |

By the time the post mistress arrived, the building was packed to the ceiling with packages. We helped her search through the stacks on stacks on stacks of boxes to find one of the two for us. The food arrived, but, due to shipping confusion in Anchorage, our boat would arrive four days later.

We visited with Al, built rock towers along the river bank, enjoyed pizza night with Al (he wore a Pizza My Heart shirt), hiked up a nearby peak, played midnight basketball with the village kids, and ate lunch with aschool teacher’s family.

To provide some flexibility, we built an eight-day loop in the Arrigetch, home to the Brooks Range’s best rock climbing, into the middle of our route. For the first few days I was disappointed and angry about the delay in Anatuvuk. I REALLY wanted to explore the Arrigetch! By the fourth day, however, I realized how valuable our time here was: we had a rare period of time free from obligations and distractions, and I learned a great deal about Brooks Range geography, history, and culture.

![]() |

| The ranger station cost $1,000,000 to build. |

![]() |

| Our camp at the end of the airstrip (white pyramid shelter) |

![]() |

| Diesel, flown in and heavily subsidized from north slope oil revenue, powers Anatuvuk Pass generators. |

![]() |

| The 8 x 8 Argo is the vehicle of choice for hunting. |

ANATUVUK TO WALKER LAKE (160 miles)

This was the driest summer in the last two decades and it followed one of the driest winters on record; the John was running low and bony. We paddled through slow meanders outside of Anatuvuk, dragged the boat through the majority of a four-mile long rock garden, and enjoyed blissful Class II paddling on crystal clear water farther downriver.

Among other ways, we knew we were getting farther from Anatuvuk because the frequency of aluminum can sightings, resulting from the village’s love for soda, was decreasing. We switched muscle groups and walked up Wolverine creek in the creek, seeing hundreds of small fish and stepping over and on thousands of boulders, almost all of the 23 miles to the first pass.

![]() |

| We walked the boat through the majority of this four mile rock garden. |

![]() |

| 11 p.m. views of the Arrigetch. Let's camp here! |

Sarah ripped her pants in the brush near the top of a pass and took them off to fix them before they tore further. A brown bear strolled up about 20 feet away. He/she caught us off guard, with our packs splayed open, and Sarah’s pants down. “Hey bear, sorry to bother you. We’re just passing through. Trying to repair our pants.”

Due to her greater respect (which is not to say I lack respect), Sarah became our wildlife relations manager: She directed my behavior, oversaw the handling of bear spray, led us in the creation of audible deterrents, and dictated our terrestrial and aquatic navigation when large mammals were present.

Over time, our audible deterrents evolved from "Hey Bear" to "Hey Deer" to "Hey Dear," to "Hey Sexy,""Hey Baby,""Hey Sugar Mamma,""Hey Baby Cakes," etc.

Once the snow melts, water in arctic creeks comes primarily from melting tundra. Walking in the Nahtuk almost all the way to the Alatna was very cold. Our legs and feet were refrigerated. Numb. Stiff. Hard to feel what was going on down there. A narrow, boulder and log choked canyon sent us several hundred feet up steep slopes with thick brush. A few minutes passed before Sarah noticed the alders had snatched the lower third of a trekking pole. This prompted a unpleasant, obsessive hunt for the foot-long piece of carbon fiber and a resolution to wrap the bottom sections in pink duck tape when we returned home.

![]() |

| The Nahtuk running low (left) One of the canyons we climbed around (right) |

![]() |

| Walking in the lower Nahtuk. |

![]() |

| Wading in the lower Nahtuk--exhilaratingly cold and spooky. |

When we reached the Alatna we walked hundreds of feet across gravel bars to the green, slow water. The river was shockingly LOW. We stopped paddling to admire, discuss, and record video of the first contrail we saw in two weeks. The white streak was a reminder of the global economy in which were, at the moment, connected to only via our clothing and equipment.

![]() |

| Blowing up on the Alatna. |

![]()

We were frigid cold the first day of paddling in the rain with temps in the low 40’s. Our legs and butts were soaked because we neglected to put on our rain pants in the morning. Big mistake. Our hands were not working well—it took five minutes to open the boat’s inflation valve, which is normally a simple twist of the thumb and forefinger—because we didn’t start the day wearing our rain mitts. Big mistake. Sarah was borderline hypothermic, which gave me a rare opportunity to convince her to take big bites of cheese straight from the two pound block. This would never happen normally, as she hates the sticky feeling of biting into a chunk of cheese and the resulting, persistent smell from cheese particles that remain jammed in your teeth and gums. But we both warmed up from eating and running back and forth on the gravel bar—enough to agree to get back in the boat and keep paddling. A drysuit would have turned the day, and though we didn't know it yet, many subsequent days, into Type 1 fun.

Rain continued as we left the Alatna and crossed west through unnamed, seldom visited watersheds. The brush was far denser than expected and we became soaked from thrashing and bashing. To combat the now mid thirties temperatures, we shoved chocolate and cheese into our mouths.

The terrain was mysterious with ever-shifting clouds, deep spongy mosses, willows yellow from the onset of fall, and steep peaks with tiny remnants of glaciers. At 11 p.m., as it was beginning to get dark, we were climbing up steep grassy slopes near the top of a pass when we realized we were in a bear den. We could see the many places the bear(s) had laid down and were overpowered by a creepy, eerie feeling. Another way to phrase it is: downright terrified. But we were exhausted and didn’t want to drop back down and spend an extra hour schwacking up another way through the twilight. So we kept climbing up the steep, wet mountain, and spoke to the bears with utmost sincerity: “Hey bear, we’re sorry to walk through your home. We’ll be over the pass in ten minutes. Please let us by. We’re very sorry to bother you!”

The next day, we put on soaking wet clothes, schwacked down to the Kobuk, paddled gorgeous blue waters while watching a huge bald eagle twirl above us, schwacked a few more miles through bogs to Walker Lake, then paddled a few miles to our resupply point at the Helmericks house on Swan Island. We arrived, bone tired, out of food and fuel, at 11 p.m. to the sound of our friend Richard Baranow’s hammer.

![]() |

| Mid 30's and soaked. Brrr. |

![]() |

| 11 p.m. paddling on Walker Lake...almost to Swan Island! |

WALKER LAKE (0 miles)

We spent two and a half days resting, eating, and repairing gear at the Helmericks' home. We showered, washed our clothes in the sink, made four repairs to the boat, patched our wind and rain pants, taped a large tear in the groundcloth, repaired a PFD, and the lace loops on Sarah’s shoes. For breakfast, we cooked potatoes, eggs, and sausage Richard flew in. YUMMO! For dinner: hamburgers, beer, and ice cream! YUMMO! We even stayed up to 2 a.m. sitting in a couch watching a movie while eating popcorn and brownies! YUMMO! All in a house on an island, in the middle of a lake, in the middle of the largest contiguous Wilderness area in the world.

There’s nothing else like the Helmericks' home in the Brooks Range. It started in the 1940’s when Bud and Connie dragged a canoe up hundreds of miles of rivers and spent a winter in the cabin they built with hand tools. They crossed over the range the following spring, floated 300 hundred plus miles north on the Coleville to the ocean, and spent a summer with the eskimos. They became some of the first white people in Prudhoe Bay. Bud developed into a big name hunting guide and brought people like L.L. Bean to the cabin. They raised children there and, later, Bud built a two-story house on top of the cabin. One winter they snowblowed a gigantic runway on the lake so a large plane could bring in building materials. The couple wrote a series of popular books including "We Live In the Arctic,""Our Summer With The Eskimos,""Our Alaskan Winter,""Flight of the Arctic Tern, and "The Last of the Bush Pilots."

Richard has worked on the house for the last six summers. This year, he built a gorgeous 25’ x 15’ deck on the second story. With an elaborate winch system of his design, we helped him install the stairs and a solar panel to trickle charge the house batteries. Staying there and seeing artifacts of the old Alaska was an absolute privilege and a highlight of the trip.

![]() |

| The Helmericks' guest cabin, built in the 1950's, decorated with our freshly sewn, glued, and washed gear. |

![]() |

| 2 a.m. bonfire with Richard. |

![]() |

| Sarah carried these rocks between 50 and 130 miles! Richard flew them back for her. |

![]() |

| Protection from my poor casting. |

WALKER LAKE TO AMBLER (197 miles)

Due to the abundance of glaciers, there aren’t many large, clear rivers in Alaska. The Kobuk is one of the state’s beauties. The upper part of the river was absolutely fantastic. We floated through crystal clear water over tens of thousands of chum salmon, grayling, char, and sheefish.

Each evening we saw five to ten brown bears walking the edge of the river looking for chum. Satiated by the abundant food, they gave us nary a glance.

Seagulls dive-bombed the small black boat and its colorful paddlers. The paddlers deflected the assault by waving their paddles overhead. Resorting to other methods, several bold gulls launched aerial fecal attacks. The paddlers watched white excrement fall through the air and land nearby. Plop. Again. Plop. Later, an expert marksman hit the spray deck between the paddlers, missing them by a few inches.

We portaged around the upper Kobuk canyon and lined the boat around the class III parts of the lower canyon. Later that day we encountered people for the first time in 15 days: two high-level fly fisher folk from Anchorage. We gave them a pixie, a type of fishing lure, that we found outside of Anatuvuk and they gave us several homemade flies and fancy hand line—the ultimate ultralight fishing setup. Unfortunately, for various reasons including lots of rain and the need to build a fire in order to cook fish, we never used their generous gift.

Soon, the river divorced topography and remarried a vast landscape of sinuous channels, and tundra. It was a country with big skies and big weather systems--country that nourishes Sarah’s soul. The cranes called to her. The temperatures dipped below freezing. The tundra was orange and red. As we paddled, we played hangman and 20 questions, sang songs, and watched eagles, osprey, cranes, and swans.

![]() |

| Fish camps, where (primarily) Alaska Natives catch and dry fish, became more frequent as we traveled downstream |

![]() |

| We had twenty minutes of shirts off summer paddling. It was wonderful. |

![]() |

| Avoiding the rapids (out of the frame to the left) at the end of Lower Kobuk Canyon. Note all the exposed rock. |

The gravel bars on the upper Kobuk were a rock hunter’s paradise. Every bank was filled with brightly striped, speckled, and swirled rocks of blueberry to grapefruit size. We collected six pounds worth, an exercise of great comparison and deliberation, and stopped in Kobuk (population 150) to mail them home. Someone in there told us the river was the lowest in living memory.

At some point before Kobuk, the river turned from a gorgeous delight into, for me, a boring slog. The views became rare to none, the banks became monotonous and rose ever higher above us, and the low flow made the river feel like a lake. We accidentally referred to the river as a lake. Paddling into the wind was brutal.

Our uncomfortable boat became nearly intolerable. We were kneeling for 12 hours a day with our feet twisted up underneath us, soaking in cold water. I used my paddle as a crutch to get out of the boat and as a cane for the first few minutes of hobbling around. Our feet were swollen, red, and bruised. We began to take stretch breaks every 60–90 minutes. I didn’t regain feeling in all of the toes on my left foot until a week after we got home.

![]() |

| Sinuous! Note the old channels and 8/19 campsite label. The photo below shows that site. |

![]()

![]() |

| Sometimes we found it faster to pull the boat. |

AMBLER TO KIANA (107 miles)

Our extra day at Walker Lake and the slow river—we’d averaged around 3.5 mph when we estimated at least 5 mph—put us behind schedule. Even if we paddled a minimum if 12 hours per day we estimated there wasn’t enough time finish to go to Kotzebue. I wanted to bail—to fly to Kotzebue and then home, and spend a few days cooking nice meals and relaxing indoors before Sarah left for Utah. She, however, insisted that we continue what we set out to do. We had a hard talk, packed up our copious quantity of tip-top quality resupply food, repaired an eight-inch tear in the boat’s “kneeling dragon,” and decided to voyage onwards to Kiana, the closest village to Kotzebue. From there, we would hop on a plane to Kotzebue ($160) before flying commercial to Anchorage.

One evening I wrote:

Quiet. Immense quiet. Huge wilderness. Nothing threatening. Aching body. Sitting up hurts. Always want to lay down. Loving the uncertainty and anticipation of new food.

The Great Kobuk Sand Dunes are the star attraction of Kobuk Valley National Park. I was expecting a trail from the river with a sign. Neither of those existed. The first place we pulled off the river was a wolf den—hundreds of prints and myriad trails through the brush—so we began the mild three-mile walk from farther downstream. When we got home I called the park service and learned they estimate 60 people visit the dunes each year. Most years everyone flies in and stays only a few minutes. The other visitors we saw on the river—canoeists with boats and supplies that made our setup look like a jail cell—had no interest in schwacking and continued downstream saying, "We've seen sand dunes before."

![]() |

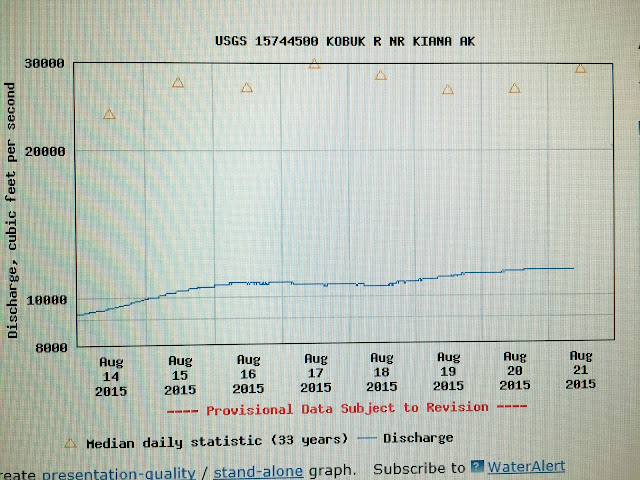

| The Ambler school let us use their computer lab to check the stream gauge in Kiana. The river was running at ~12,000 cfs when it’s normally around 30,000 cfs! Flow, not slope, is what carries a boat downstream on the lower Kobuk; the river only drops six inches per mile. |

![]() |

| The main road in Ambler. Plastic is easier to fly in than pavement. |

![]() |

| On this section, we ate better than we do at home: Adventure Appetites’ reindeer sausage scramble, beef curry, chicken chipotle enchilada, fresh oranges, olives, cocoa nibs, mulberries, fancy salami, and smoked maple sardines! |

![]() |

| We became very excited when we saw this 200 ft. tall bank. |

![]() |

| I wanted to bring this home. The decision-making process took 45 minutes. |

![]() |

| Why, yes, I'd like some sun-dried tomatoes with my olives and salami and cheese and crackers and chocolate! |

![]() |

| Great Kobuk Sand Dunes |

KIANA TO KOTZEBUE(58 miles via airplane)

We enjoyed aerial views of the Kotzebue Sound on the Bering Air flight to Kotzebue. The city, population 3,200, was gigantic compared to the villages we’d visited. We saw pavement for the first time in 32 days. We camped in someone’s yard. We were tired.

![]() |

| Our extra day at Walker Lake and the low river put us behind schedule. We flew from Kiana to Kotzebue. |

![]() |

| Happy and tired, camping in someone's yard in Kotzebue. |

HOME

Returning to civilization took considerable adjustment. Sarah woke up at our Eagle River cabin and briefly panicked because there was a roof over her head. “What is this?! Where are we?!” I took another week to transition before going back to work. She returned to hot and sunny Salt Lake City, where she complained about the 60-degree temperature change, criticized the impracticality of people’s clothing and footwear, and chose to walk nine miles round trip to school rather than take the free bus. ![]() Follow us on instagram

Follow us on instagram